Artist Installations

On Long-term View

Houston E. Conwill, The Joyful Mysteries, 1984

Created by artist Houston E. Conwill, these seven bronze time capsules were originally buried in the Studio Museum’s sculpture garden on August 12, 1984, with the assistance of ten New York City school children. The capsules contain confidential testaments by seven distinguished Black Americans: visual artist Romare Bearden (1911–1988); historian Lerone Bennett Jr. (1928–2018); the first African American mayor of Gary, Indiana, Richard Gordon Hatcher (1933–2019); judge and legal historian A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. (1928–1998); attorney, activist, and United States Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (b. 1937); writer Toni Morrison (1931–2019); and opera singer Leontyne Price (b.1927).

Conwill once said he was “especially drawn to myth, ritual, and the transmission of wisdom and culture across continents and generations.” In this spirit, the messages of The Joyful Mysteries will be opened in September 2034—fifty years after their burial, as instructed by the artist—and read to the public for the first time.

David Hammons, Untitled, 2004

David Hammons, known for his conceptual art performances, installations, and sculptures, began using the United States flag in his practice in the 1990s. In Untitled, the artist overlays the Pan-African flag colors onto the United States flag design, collapsing several identities into one.

Invented in 1920 by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the Pan-African flag consists of three horizontal strips of red (for blood), black (for the people of Africa), and green (for the abundance of the continent). The UNIA was founded in 1914 by Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) to unite the African diaspora into one nation that would strive for Black liberation. This vision and flag were adopted by other organizations in the 1960s and 1970s, including the Black nationalist and Black Power movements.

Hammons proposes that the flag is more than a symbol of patriotism—it is a contested site where histories of exclusion, perseverance, and diasporic pride converge. The placement of Untitled in Harlem accentuates the centrality of the neighborhood for the Black community, and the use of the UNIA flag colors here is fitting—the organization was headquartered in Harlem from 1918 to 1927.

Glenn Ligon, Give Us a Poem, 2007

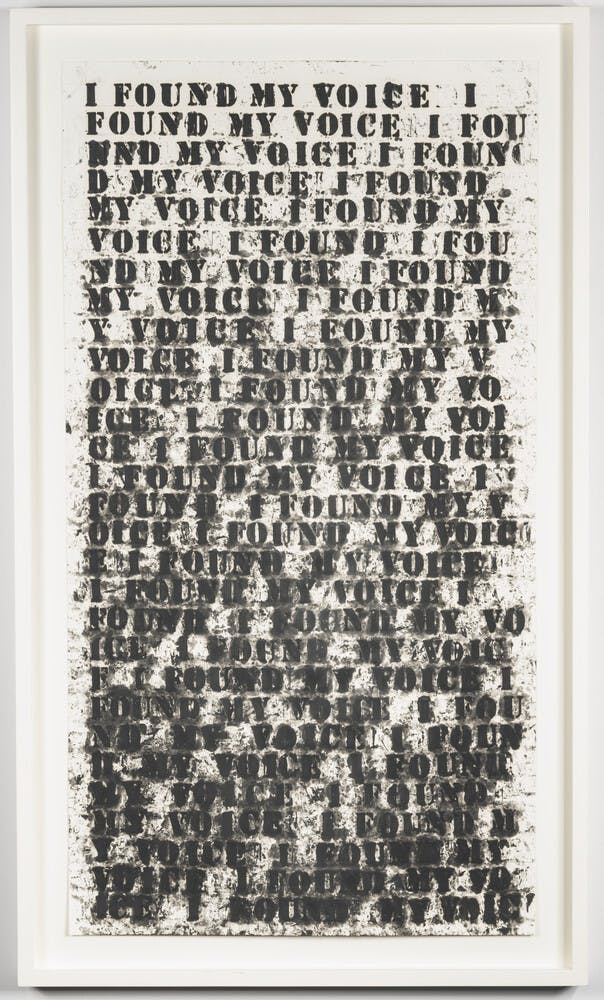

First installed in the lobby of the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2007, Give Us A Poem is inspired by a speech Muhammad Ali gave in 1975 at Harvard University. When asked by a student to give the audience a poem, Ali replied, “Me? Whee!” The phrase depicts how language, even at its most minimal, reverberates with meaning. Consistent with his practice of sourcing texts from literature, speeches, and popular culture—particularly from Black cultural figures—with this work, artist Glenn Ligon calls attention to the role of text as material, messenger, and artifact.

By repeatedly flashing "Me” and “We,” Give Us a Poem explores binaries—light and dark, presence and absence, and above all, the relationship between the self and the collective.

Artist Installations

On Long-term View

Houston E. Conwill, The Joyful Mysteries, 1984

Created by artist Houston E. Conwill, these seven bronze time capsules were originally buried in the Studio Museum’s sculpture garden on August 12, 1984, with the assistance of ten New York City school children. The capsules contain confidential testaments by seven distinguished Black Americans: visual artist Romare Bearden (1911–1988); historian Lerone Bennett Jr. (1928–2018); the first African American mayor of Gary, Indiana, Richard Gordon Hatcher (1933–2019); judge and legal historian A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. (1928–1998); attorney, activist, and United States Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (b. 1937); writer Toni Morrison (1931–2019); and opera singer Leontyne Price (b.1927).

Conwill once said he was “especially drawn to myth, ritual, and the transmission of wisdom and culture across continents and generations.” In this spirit, the messages of The Joyful Mysteries will be opened in September 2034—fifty years after their burial, as instructed by the artist—and read to the public for the first time.

David Hammons, Untitled, 2004

David Hammons, known for his conceptual art performances, installations, and sculptures, began using the United States flag in his practice in the 1990s. In Untitled, the artist overlays the Pan-African flag colors onto the United States flag design, collapsing several identities into one.

Invented in 1920 by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the Pan-African flag consists of three horizontal strips of red (for blood), black (for the people of Africa), and green (for the abundance of the continent). The UNIA was founded in 1914 by Marcus Garvey (1887–1940) to unite the African diaspora into one nation that would strive for Black liberation. This vision and flag were adopted by other organizations in the 1960s and 1970s, including the Black nationalist and Black Power movements.

Hammons proposes that the flag is more than a symbol of patriotism—it is a contested site where histories of exclusion, perseverance, and diasporic pride converge. The placement of Untitled in Harlem accentuates the centrality of the neighborhood for the Black community, and the use of the UNIA flag colors here is fitting—the organization was headquartered in Harlem from 1918 to 1927.

Glenn Ligon, Give Us a Poem, 2007

First installed in the lobby of the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2007, Give Us A Poem is inspired by a speech Muhammad Ali gave in 1975 at Harvard University. When asked by a student to give the audience a poem, Ali replied, “Me? Whee!” The phrase depicts how language, even at its most minimal, reverberates with meaning. Consistent with his practice of sourcing texts from literature, speeches, and popular culture—particularly from Black cultural figures—with this work, artist Glenn Ligon calls attention to the role of text as material, messenger, and artifact.

By repeatedly flashing "Me” and “We,” Give Us a Poem explores binaries—light and dark, presence and absence, and above all, the relationship between the self and the collective.