Domesticity

The artists in this collection explore domesticity as an artistic subject, asking, What does it mean to be “at home?” How does one make a space of one’s own, even against the odds?

This black-and-white portrait depicts Coretta Scott King in front of her home in Atlanta just five days after the assassination of her husband, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Amid national grief, she finds solace near her home—Mrs. King stands with feet firmly planted, looking toward a brighter future.

Weaving danger with domesticity, Theaster Gates recycles decommissioned fire hoses to create his Civil Rights Throw Rug 7200.45. Moved by the violence of the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, wherein policemen weaponized high pressure fire hoses to injure peaceful protestors, Gates visually connects quotidian furnishings with Black struggle to propose that inequity is everywhere and everyday in African American life.

This photograph is a part of the series "Harlem Document," in which Aaron Siskind photographed street and home scenes in Harlem. Siskind dedicated eight years to documenting the community, who were also interviewed by members of the Federal Writers' Project.

Deana Lawson often photographs her subjects in their homes, focusing on the contrasts between furniture and the figure. Responding to canonical representations of women in recline, Lawson instead highlights a woman proudly taking up space.

Inventing Truth presents a collection of imagery largely associated with Black men. By juxtaposing feminine craft with objectifications of masculinity, Adia Millett not only disrupts gendered stereotypes of artistic mediums but also reconsiders how gender manifests through interior spaces. The installation also mimics common domestic picture hanging practices.

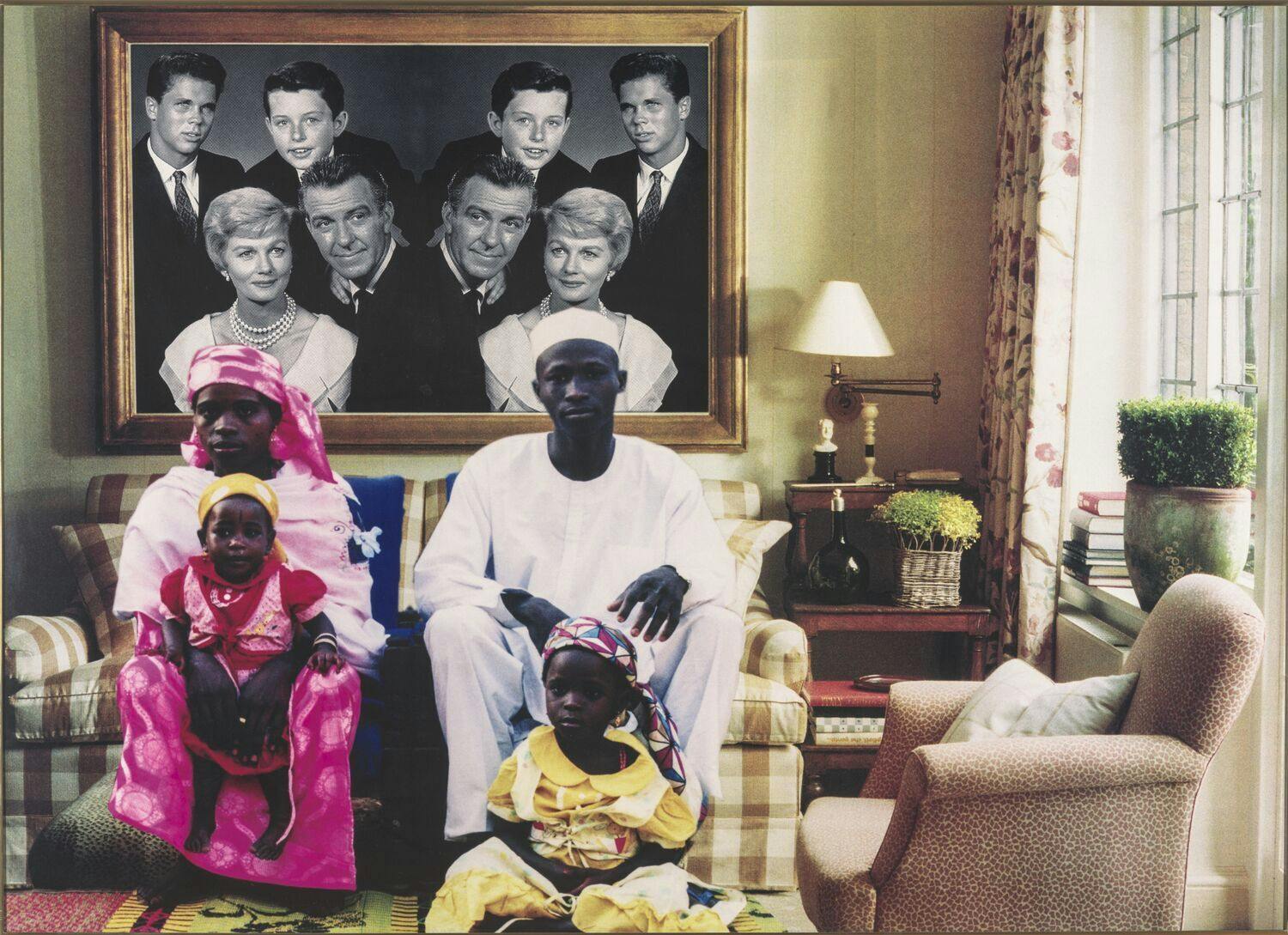

Iyali (family) proposes a cultural connection across disparate nuclear family homes. Through digital collaging, artist Fatimah Tuggar frames the Cleavers, a fictional family from the 1950s sitcom Leave It to Beaver, behind an African family sitting in a suburban living room. This insertion incorporates Black families into Americana traditions at the same time that it underscores the discord between this family and the “ideal” ones depicted on television screens.