Diaspora

Scattered by migrations, voluntary and not, global Black populations have long contended with efforts to write them out of history. Countering such geographic dislocation and attempts at eradicating and looting aesthetic traditions, works by artists in this collection turn to the cultures, art, people, and geographies of Africa to convey and reclaim relationships to the continent within their work.

Diaspora was organized by Simon Ghebreyesus, former Studio Museum/MoMA Joint Curatorial Fellow.

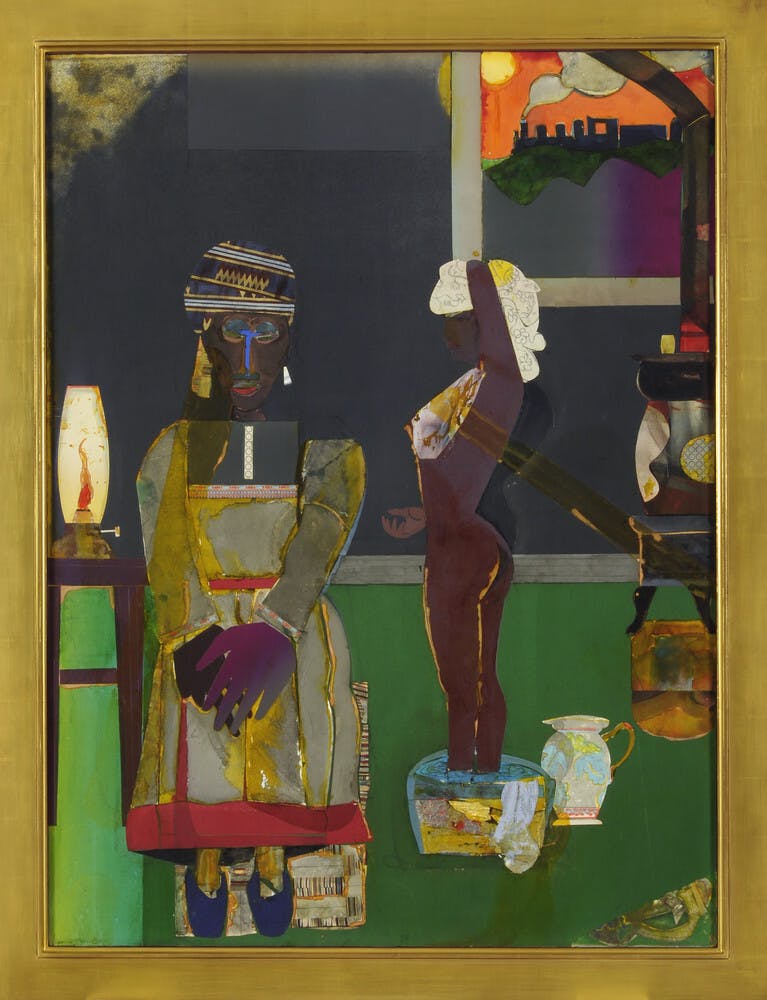

Artists like Romare Bearden, whose collage Prelude to Farewell (1981) features a figure with a highly stylized face, admired the formal qualities and expressive potential of masks.

Elizabeth Catlett’s Mask (c. 1970) adopts a loose resemblance to its African counterparts, engendering solidarity through shared cultural heritage and using the form to convey the messages found in the newspapers adhered to the interior of the piece.

Others recreated more specific traditions;

of steam irons, like the one repurposed in Steam’n Hot (1999), artist Willie Cole says, “right away I saw it as an African mask, more specifically a Dan mask.”[1] The face of the iron mirrors the almond-shaped outlines often found in the masks from this Ivorian and Liberian ethnic group.

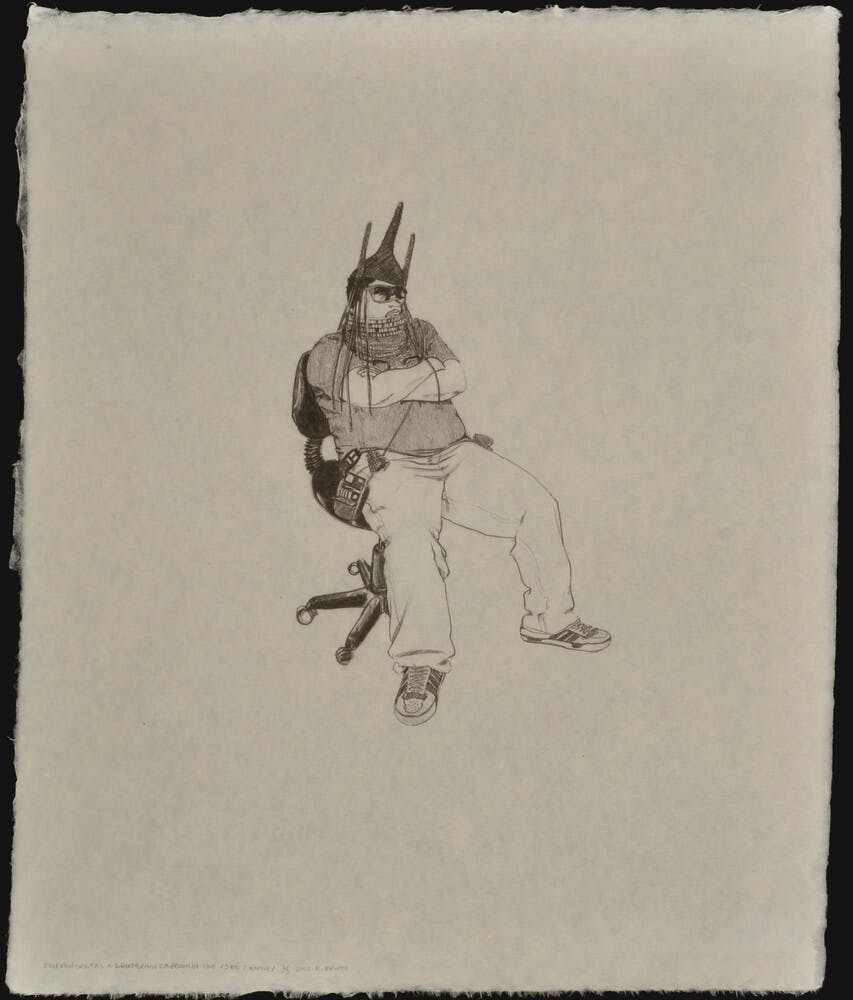

Similarly, Robert Pruitt’s Self Portrait as a Great Benin Emperor of the 23rd Century (2007) inscribes the artist, sitting in an office chair, with a regal Beninese heritage that at once looks to the past and future, as the title suggests.

Turning to the northeast of Africa,

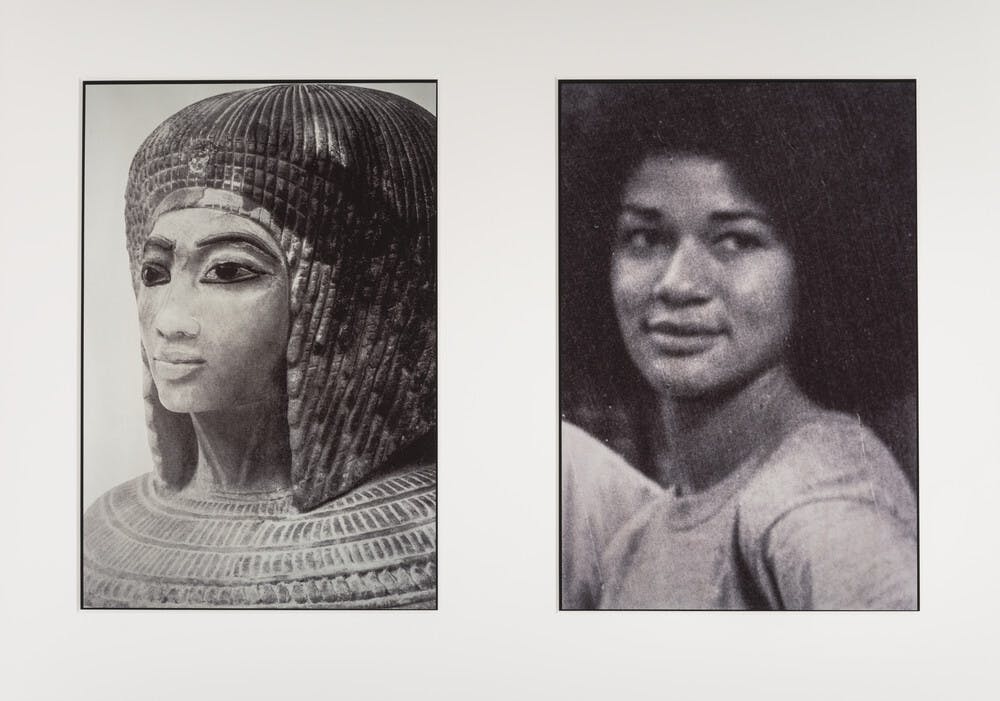

Lorraine O’Grady’s Sisters II (L: Nefertiti’s daughter Merytaten, R: Devonia’s daughter Candace), from the "Miscegenated Family Album" (1980/1988) pairs an image of the artist’s niece with one of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti’s daughters, tethering a contemporary African American existence to an ancient African one.

Dave McKenzie’s They Dreamed of Nefertiti's Holiday (2011) collages images of the Nefertiti bust with cutouts from other contemporary sources. In spanning time and space to source the elements of his collage, McKenzie draws royal Egyptian history into the present.

Likewise, Avel C. de Knight’s Untitled (from Pyramid series) (c. 1974) offers a glimpse at Egyptian architecture with a Black man reclining in front of a pyramid and passing travelers.

Zooming out to view the continent from afar,

Fred Wilson’s Atlas (1995) envisions the diaspora, marked by pins on a globe upheld by a stereotypical minstrel figurine recast as the Greek Titan Atlas.

Fatimah Tuggar uses a composite vantage point in her print

Untitled (Army) (1996), which presents a troubling scene of miniature soldiers encroaching on a woman making food with her children. Rather than showing movement out of the continent, like Wilson, Tuggar depicts an invasion in, prompting us to consider just one of the many reasons behind the global dispersal of Black people.

Lastly, Malick Sidibé’s The Wannabe Musician Behind His Car (1971) offers a glimpse at post-Independence Mali. A young man, guitar in hand and smiling wide, leans on the back of his car. He emblematizes an Africa in flux, with numerous nations fighting for liberation from colonial rule. He is confident and he is free.

Diaspora was organized by Simon Ghebreyesus, former Studio Museum/MoMA Joint Curatorial Fellow.