The Other Side of Light

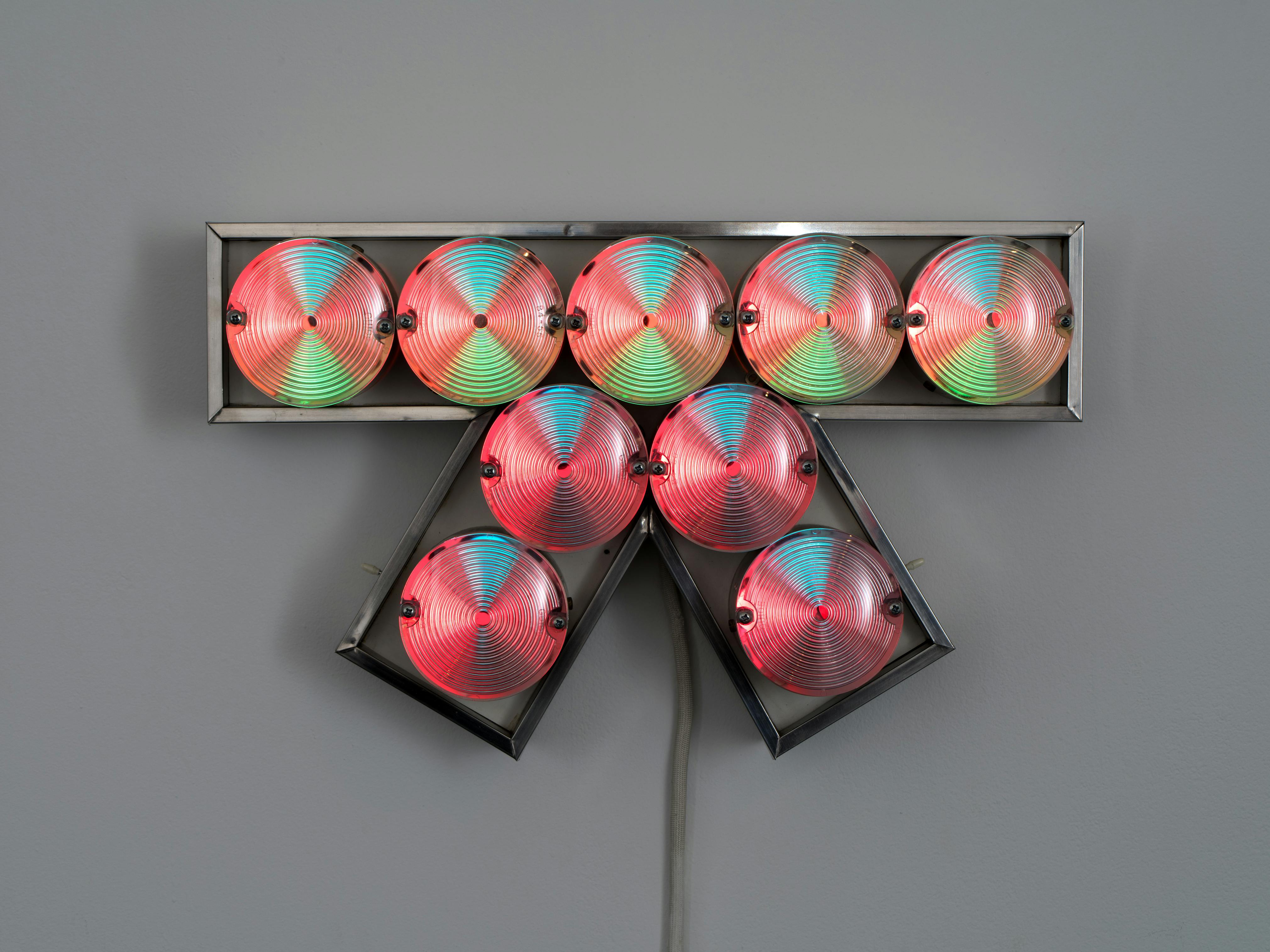

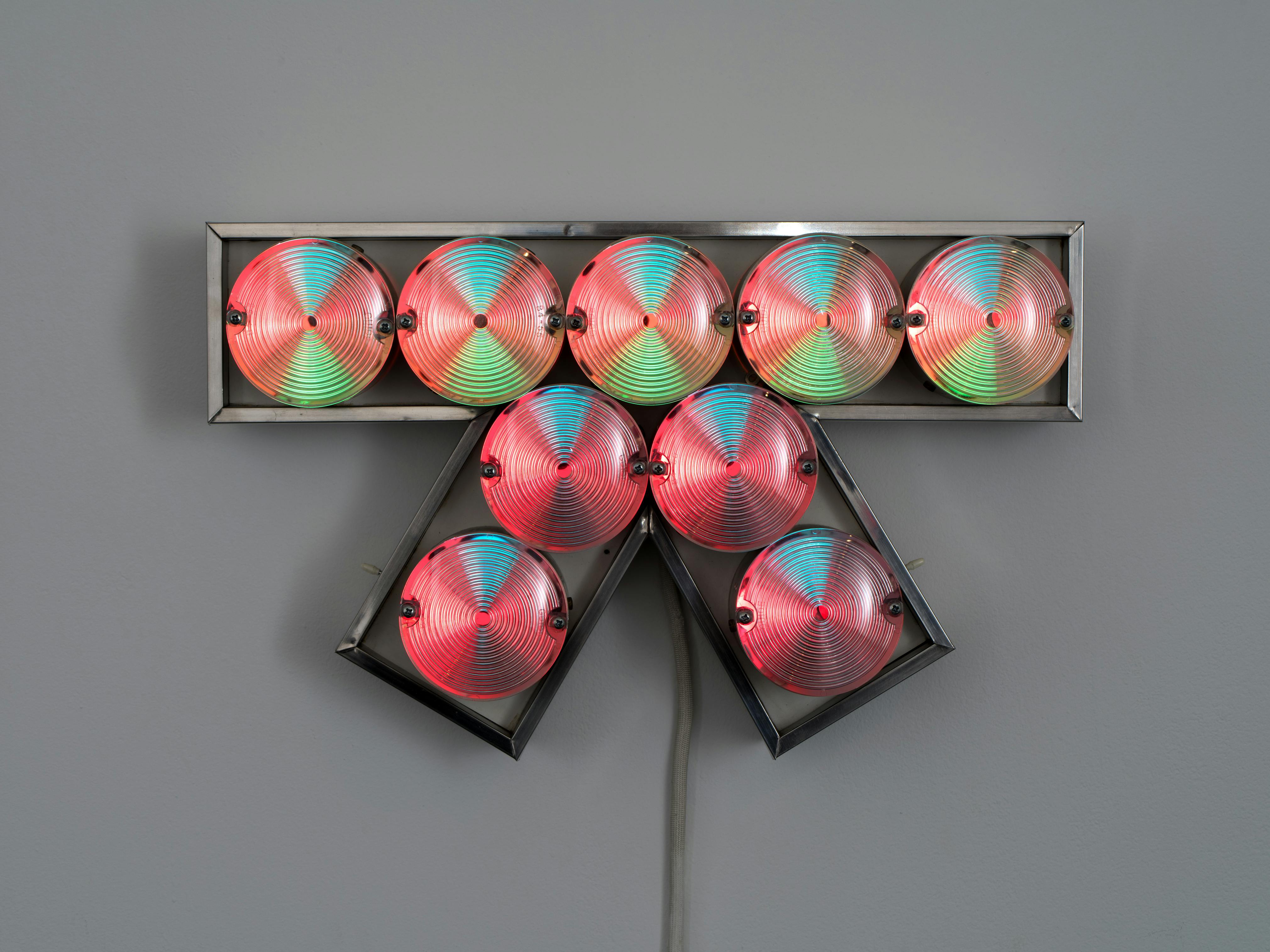

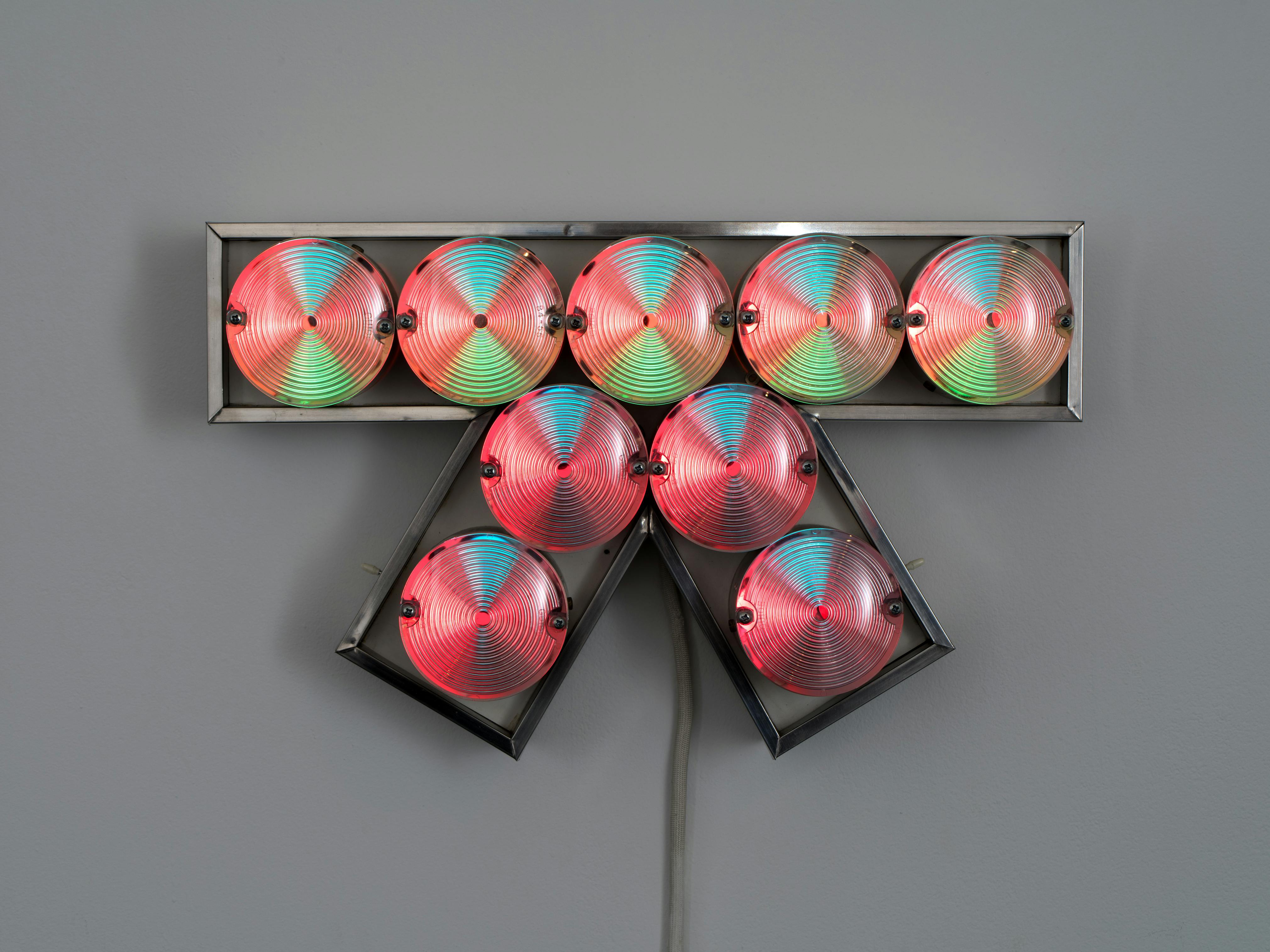

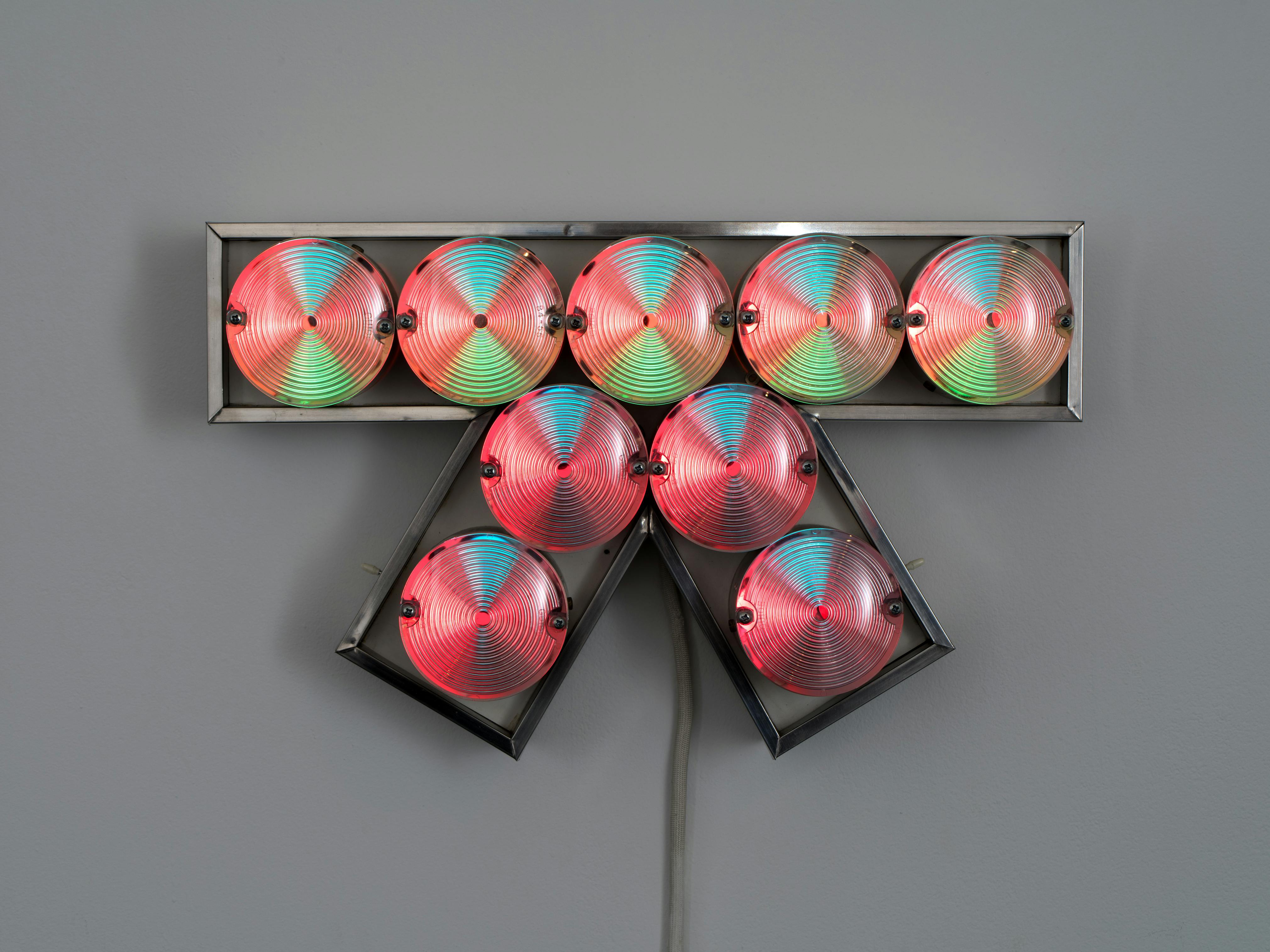

Tom Lloyd, Narokan, 1965. Aluminum, light bulbs, and plastic laminate, 11 1/2 × 18 1/2 × 5 in. Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Darwin K. Davidson 1988.3. Photo: John Berens

Tom Lloyd, Narokan, 1965. Aluminum, light bulbs, and plastic laminate, 11 1/2 × 18 1/2 × 5 in. Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Darwin K. Davidson 1988.3. Photo: John Berens

Excerpted from Tom Lloyd

Artist, activist, and community organizer Tom Lloyd (1929–1996) was an early pioneer of using electric light as an artistic medium. Collaborating with an engineer at the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), Lloyd developed a highly experimental and technologically advanced art practice in the 1960s that challenged popular understandings of the work and role of Black artists. His pioneering artwork was the focus of the Studio Museum’s first exhibition, Electronic Refractions II, in 1968. Based on extensive new scholarship and intensive conservation work, Tom Lloyd will explore twenty years of the artist’s career, including his pivotal contributions to the intersection of art and technology, and pay tribute to his activism with the Art Workers’ Coalition and his founding of the Store Front Museum, the first art museum in Queens.

For Studio, we share an exclusive excerpt from the first catalogue on the artist, copublished by the Studio Museum and Gregory R. Miller in conjuction with the historic exhibition. In this excerpt, the artistNikita Gale takes an epistolary approach to examining the artist’s frame of mind

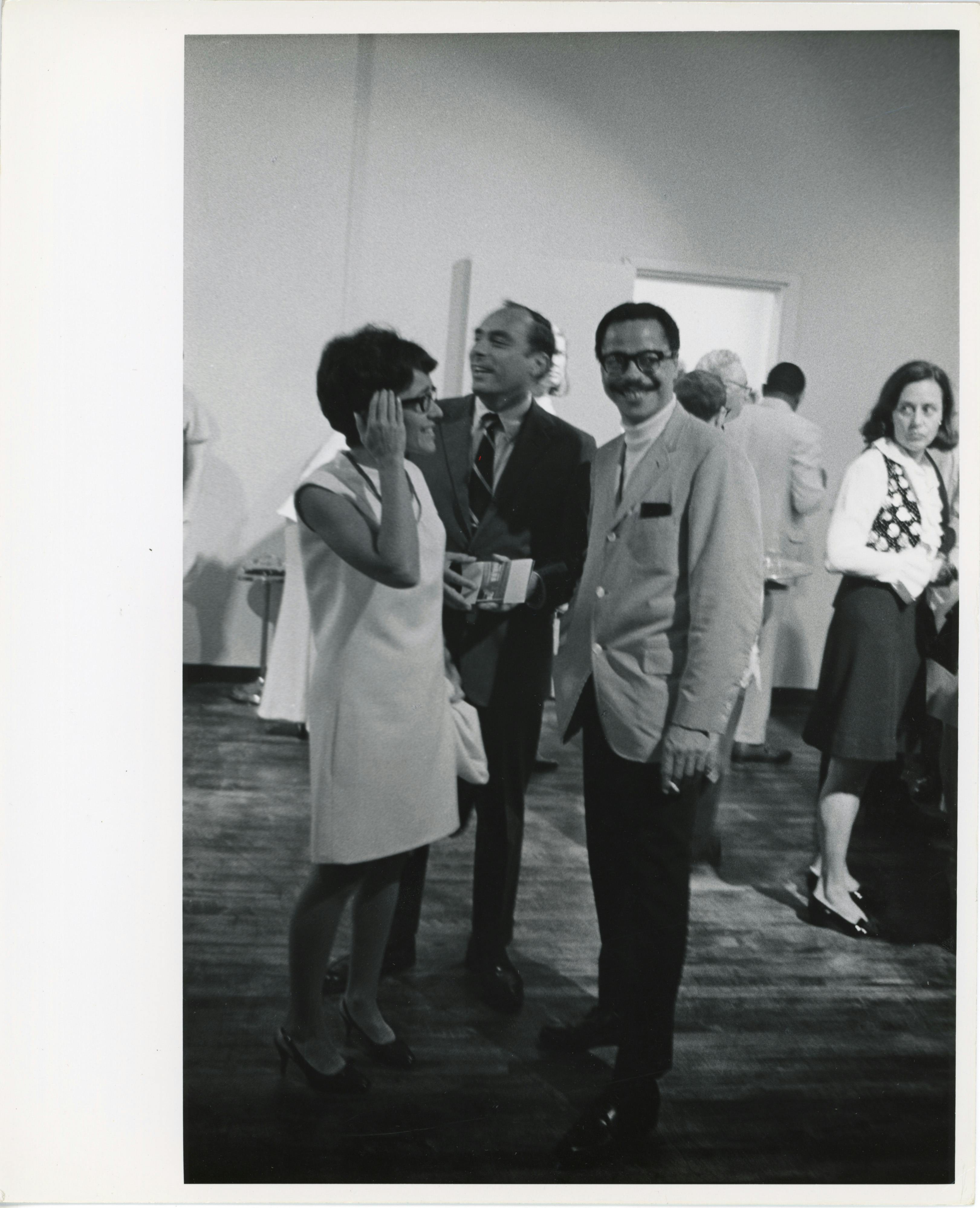

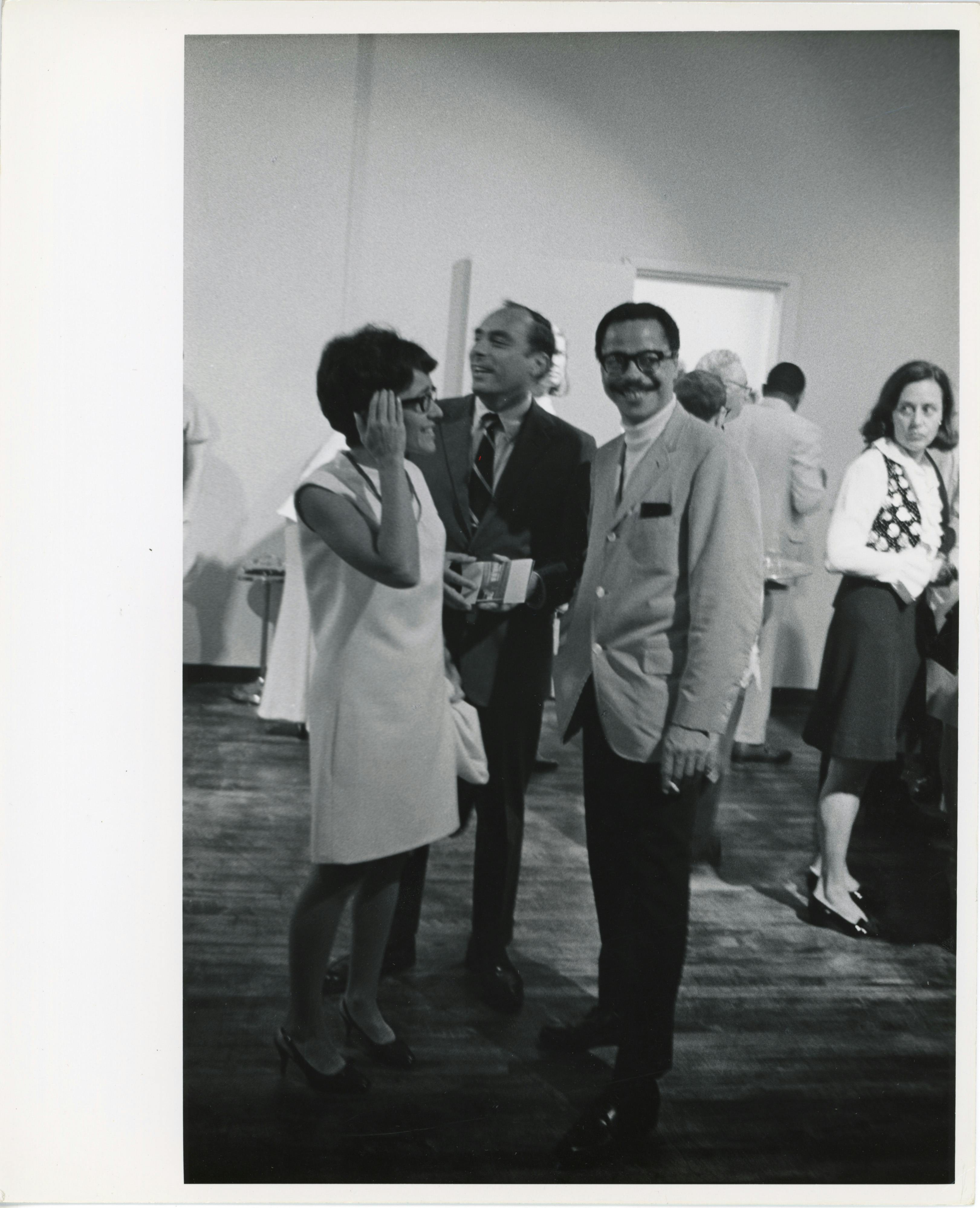

Tom Lloyd and others pictured at the Electronic Refractions II opening, 1968. Photo: Omar Kharem

When I was in elementary school, I recall learning that a Black man named Garrett Morgan invented the three-signal traffic light. I haven’t come across any mention of this connection between your work and this historical fact, but it seems important to point out for two reasons:

1. Your insistence that a thing can be “Black” merely because a Black person had a hand in creating it and

2. Your obsession with infrastructure

These two reasons seem crucial to getting your work, because you believed that the structure (time, space, race, class) through which the work is made is crucial to what the work is and what the work does.

Serious stuff.

But when I’m looking at a video of Narokan, I can feel you having fun in your studio, being curious, being totally turned on. It feels familiar, personal. I completely get it. It feels like I’m catching a glimpse of some kind of game or party.

What kind of world would this be, where streetlights moved like this and at this pace? How would the people move with them? That’s what really gets me about this work. It makes me imagine a world gone wild, filled with pleasure and movement like the scene in The Wiz where Diana Ross, playing Dorothy, first enters the Emerald City. It’s a massive disco filled with the hottest people you’ve ever seen, and it’s controlled by the booming disembodied voice of the Wiz, played by Richard Pryor, whose power first manifests as light. When we hear the Wiz’s voice thunder, “I thought it over and green is dead / ’Till I change my mind, the color is red,” the entire scene is flooded with red light, creating the illusion that all of the citizens are now wearing red. That’s the thing about light—it gets on you, it changes how you see and how you’re seen. It shifts attention. Attention seems to be a primary concern in your work. Traffic lights, brake lights, headlights—all of the ways that people communicate through light signals, specifically in relation to streets and cars. It’s a technology that makes navigating a city safer, more efficient. The light makes moving easy. It tells people where you’re going and what you’re about to do. It gives the street a voice that tells its inhabitants when to stop and when to go.

Your work also feels like songs or games. I’m reminded of playing the memory-based electronic light-and-sound game Simon when I was a child. The game came out in the late 1970s and remained popular in the 1980s and 1990s. It was a circular black plastic case with four different- colored panels—red, blue, yellow, green—that would light up. Each panel had a dedicated tone that would play when it lit up. The objective was to repeat the pattern the game produced; each time you repeated the pattern correctly, one additional “step” or note would be added to the sequence. It was my favorite game, and I probably only stopped playing it around the time I got a Nintendo NES. I do have vivid memories of taking apart the Simon and reassembling it a few times to try to understand how it all worked. But you were doing this with an entire world: the most familiar urban landscape.

Back to the party. These sculptures have a pulse. This work is alive. That word, “alive,” feels important, because in your own writing you’ve referred to the “anti-life posture” of Western arts institutions, namely museums. There is some quality in your work that inspires me to speak to you as if you are alive too.

From what I’ve learned from your writing and transcripts—your own words—political action and social progress were never moving fast enough for you. You needed speed for yourself, for your descendants, but also for the reception of your work. Is there any medium faster than light?

Tom Lloyd, Narokan, 1965. Aluminum, light bulbs, and plastic laminate, 11 1/2 × 18 1/2 × 5 in. Studio Museum in Harlem; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Darwin K. Davidson 1988.3. Photo: John Berens

How could you possibly spend time on something as inconsequential as light sculptures when politicians and activists are being murdered in broad daylight? How could you possibly not? While visibility isn’t compulsory for imagination, It certainly makes it a lot easier—I have always been struck by the fact that 70 percent of the sensory receptors in the human body are found in the eyes. You were working in this way because you wanted to. And that part—making conceptual and aesthetic choices based on your individual interests and desires—was the project. That was your “Black art.” To show, by example, that you can make art that doesn’t have to do all the work of a much larger political project; the art object is one piece of a larger political infrastructure. Far out.

You always pointed to the importance of having the attention of children because they need to know what is possible. Is there anything more anti, more radical, more contrary, than a decentered social position laying claim to something as universal, as ubiquitous, as necessary to vision, to most biological life on the planet, as light?

In theory, light can travel forever until it encounters a material that can absorb it. Somewhere out here we’re finally catching up. Blackness isn’t the absence of light, but light’s total absorption. When light is absorbed, that energy doesn’t just disappear. Sometimes it even gets used as fuel.