Texas Isaiah in Conversation

02.17-02.28.2022

Online

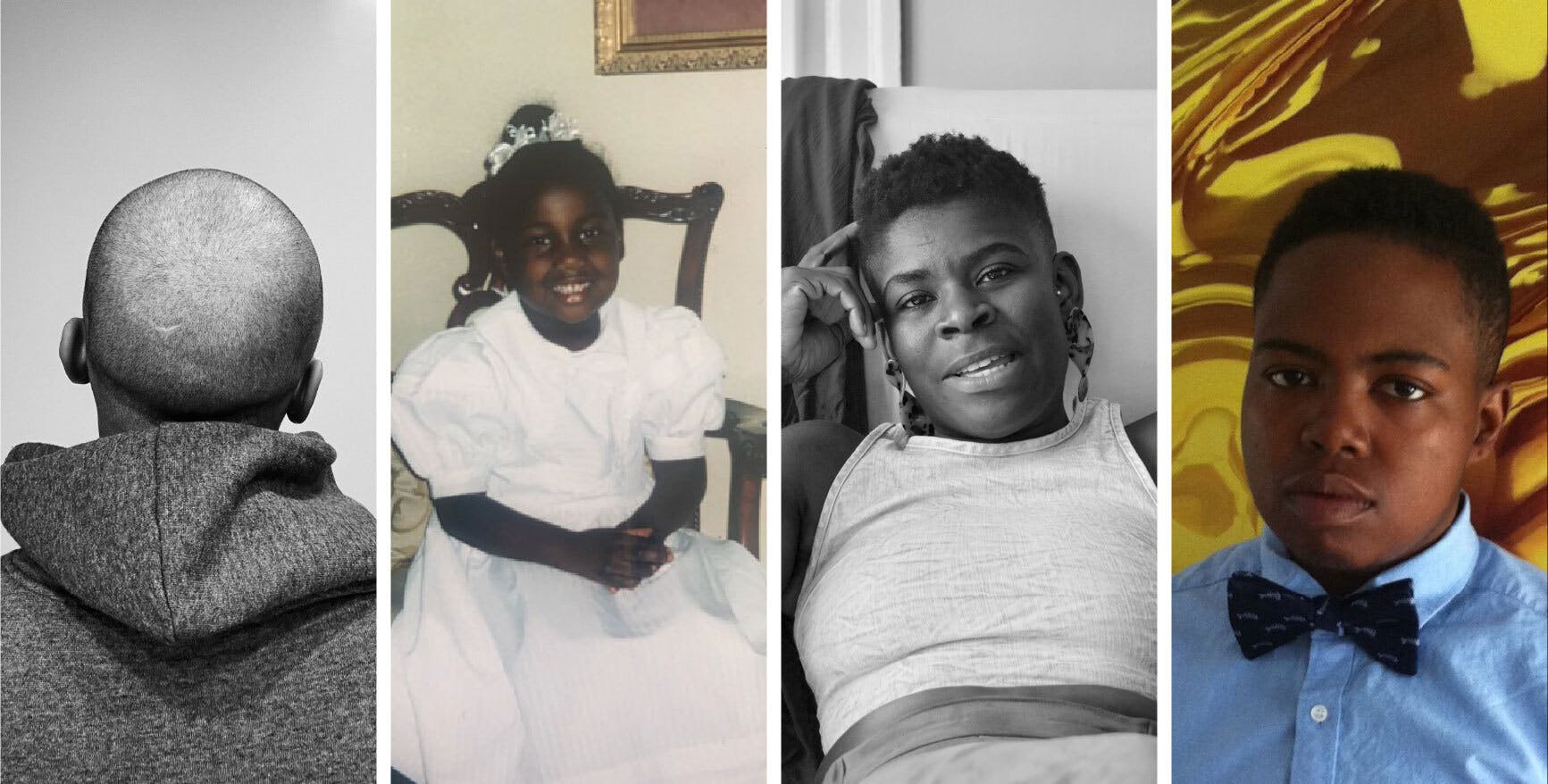

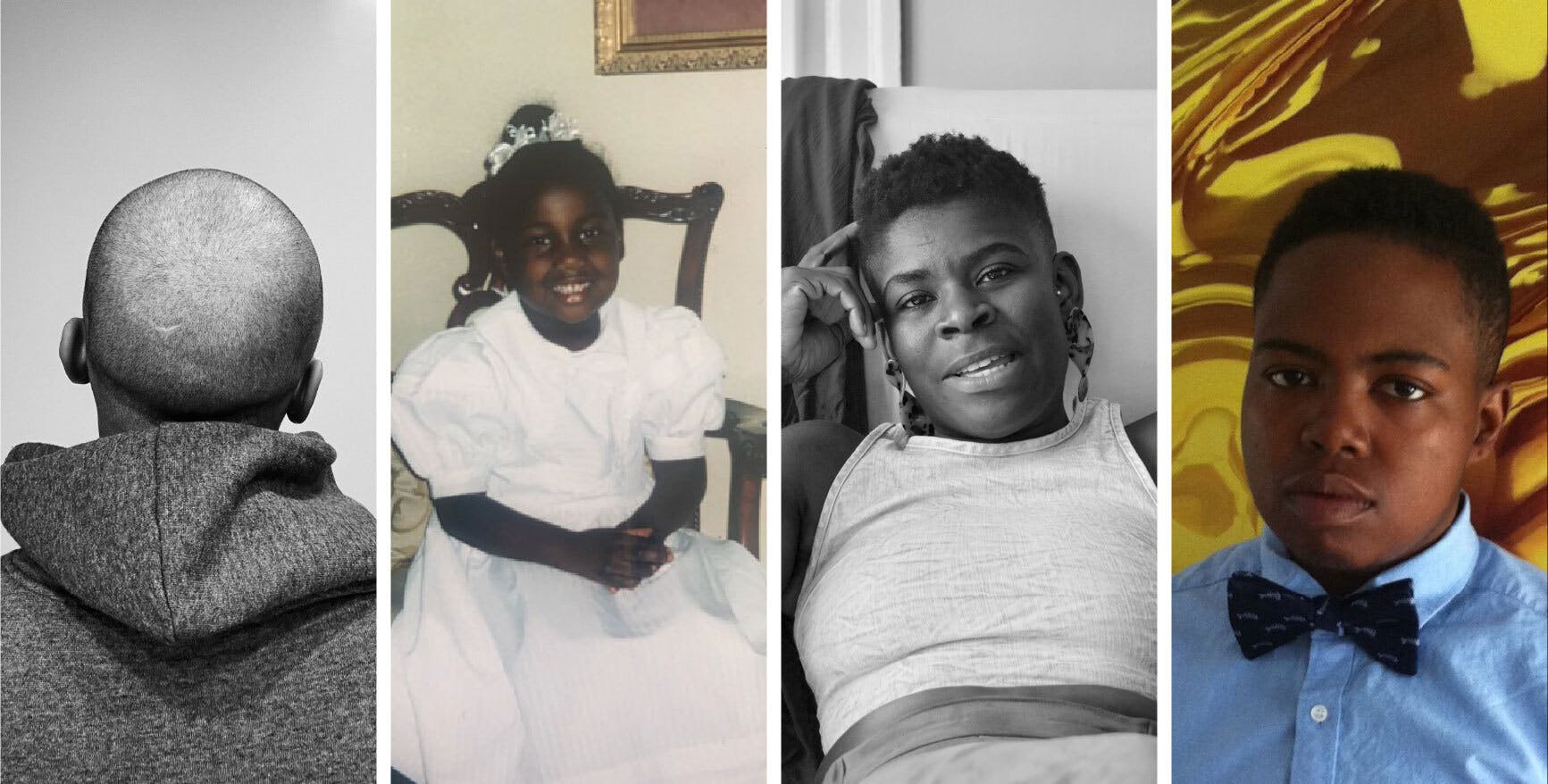

2020–21 artist in residence Texas Isaiah shared digital space with photo sitter and collaborator Bearboi, artist and thought partner Terrell Brooke, and scholar and writer C. Riley Snorton for a conversation that expands the blueprint for a collective archive of Black trans lives. During their time together, the group reflected on the following questions and more:

What does it mean to be an individual with multi-faceted experiences of Black girlhood but who bloomed otherwise? How do these experiences create a “fixture” for masculinity and gender? How can our creative work be used as healing mechanisms and dedications to ancestors (who are named and not named?) What does it mean to call ancestors into a space? What are the many consequences of Black transmasculine visibility? Are Black transgender people allowed the right to opacity? How can we define blackness (feminine, masculine, or neither) outside of labor? In what ways can we honor friendship, communion, multi-dimensionality, and intuition as strategies for authenticity?

Texas Isaiah in Conversation is presented on the occasion of (Never) As I Was: Studio Museum Artists in Residence 2020–21, held at MoMA PS1 while the Studio Museum constructs a new building on the site of its longtime home on West 125th Street.

Texas Isaiah Conversation Reading References

In Conversation: Resources

Audre Lorde, The Black Unicorn: Poems, W. W. Norton & Company, 1978 Ki-Tay Davidson, “Championing our Communities: An Open Letter,” Obama White House Archives, August 15, 2013 C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn, “Trans Necropolitics: A Transnational Reflection on Violence, Death, and the Trans of Color Afterlife,” TransReads.org, March 18, 2019 Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, “On Opacity,” Transcultural English Studies, 1990, shifter-magazine.com

In Conversation: Beloved Transcestors Body Copy

In Conversation: Beloved Transcestors

This is a record of transgender ancestors’ names and life stories that were mentioned and uplifted during Texas Isaiah in Conversation. The term transcestor was coined in 2009 by Lewis Reay.

In Conversation: Beloved Transcestors

Texas Isaiah Conversation Bios

Participant Bios

Texas Isaiah [he/they] is an award-winning, first-generation North American, visual narrator born in East New York, Brooklyn, and currently residing in Los Angeles. As an autodidact, Texas Isaiah's method prioritizes the endless possibilities of an adequate care system and a more thoughtful and compassionate visual world. In 2020, Texas Isaiah became one of the first trans photographers to photograph a Vogue cover (Janet Mock, Patrisse Cullors, Jesse Williams, and Janaya Future Khan) and a TIME cover (Dwayne Wade and Gabrielle Union-Wade). He is one of the 2018 grant recipients of Art Matters, a 2019 recipient of the Getty Images: Where We Stand Creative Bursary grant, and a 2020–21 artist in residence at The Studio Museum in Harlem.

Bearboi (they/xe/he) is a Black trans photographer and visual content creator from Prince George’s County, Maryland and is currently based in Minneapolis. Their personal work predominately celebrates the beauty of everyday life at the intersections of Black queerness, allowing the underrepresented to take up space, be seen, and be heard.

Terrell Brooke (he/him) is an interdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles who works with body movement, sound design/experimentation, and vocal exercise to explore BIPOC queer feminist theory. Terrell’s most recent works, from rhythmic multi-genre sets to abstracted soundscapes, seek to explore notions of resiliency and femme embodiment and to amplify queer narratives.

C. Riley Snorton is a writer, scholar, and advocate. He is the author of Nobody is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low (University of Minnesota Press, 2014) and Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (University of Minnesota Press, 2017). He is also the co-editor of Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value (MIT Press, 2020).

Texas isaiah Resources, References & Inspirations

Resources, References & Inspirations

Please explore the following materials offered by Texas Isaiah and his conversation partners.

Reading List by Texas Isaiah

Texas Isaiah Links

2021 AIR Funder Credits

The Studio Museum in Harlem’s Artist-in-Residence program is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts; Joy of Giving Something; Robert Lehman Foundation; New York State Council on the Arts; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Jerome Foundation; Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation; and by endowments established by the Andrea Frank Foundation; the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Trust; and Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

Digital programming is made possible thanks to support provided by the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation’s Frankenthaler Digital Initiative.

Additional support is generously provided by The New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

Texas Isaiah in Conversation

02.17-02.28.2022

Online

2020–21 artist in residence Texas Isaiah shared digital space with photo sitter and collaborator Bearboi, artist and thought partner Terrell Brooke, and scholar and writer C. Riley Snorton for a conversation that expands the blueprint for a collective archive of Black trans lives. During their time together, the group reflected on the following questions and more:

What does it mean to be an individual with multi-faceted experiences of Black girlhood but who bloomed otherwise? How do these experiences create a “fixture” for masculinity and gender? How can our creative work be used as healing mechanisms and dedications to ancestors (who are named and not named?) What does it mean to call ancestors into a space? What are the many consequences of Black transmasculine visibility? Are Black transgender people allowed the right to opacity? How can we define blackness (feminine, masculine, or neither) outside of labor? In what ways can we honor friendship, communion, multi-dimensionality, and intuition as strategies for authenticity?

Texas Isaiah in Conversation is presented on the occasion of (Never) As I Was: Studio Museum Artists in Residence 2020–21, held at MoMA PS1 while the Studio Museum constructs a new building on the site of its longtime home on West 125th Street.

Texas Isaiah Conversation Reading References

In Conversation: Resources

Audre Lorde, The Black Unicorn: Poems, W. W. Norton & Company, 1978 Ki-Tay Davidson, “Championing our Communities: An Open Letter,” Obama White House Archives, August 15, 2013 C. Riley Snorton and Jin Haritaworn, “Trans Necropolitics: A Transnational Reflection on Violence, Death, and the Trans of Color Afterlife,” TransReads.org, March 18, 2019 Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, “On Opacity,” Transcultural English Studies, 1990, shifter-magazine.com

In Conversation: Beloved Transcestors Body Copy

In Conversation: Beloved Transcestors

This is a record of transgender ancestors’ names and life stories that were mentioned and uplifted during Texas Isaiah in Conversation. The term transcestor was coined in 2009 by Lewis Reay.

In Conversation: Beloved Transcestors

Texas Isaiah Conversation Bios

Participant Bios

Texas Isaiah [he/they] is an award-winning, first-generation North American, visual narrator born in East New York, Brooklyn, and currently residing in Los Angeles. As an autodidact, Texas Isaiah's method prioritizes the endless possibilities of an adequate care system and a more thoughtful and compassionate visual world. In 2020, Texas Isaiah became one of the first trans photographers to photograph a Vogue cover (Janet Mock, Patrisse Cullors, Jesse Williams, and Janaya Future Khan) and a TIME cover (Dwayne Wade and Gabrielle Union-Wade). He is one of the 2018 grant recipients of Art Matters, a 2019 recipient of the Getty Images: Where We Stand Creative Bursary grant, and a 2020–21 artist in residence at The Studio Museum in Harlem.

Bearboi (they/xe/he) is a Black trans photographer and visual content creator from Prince George’s County, Maryland and is currently based in Minneapolis. Their personal work predominately celebrates the beauty of everyday life at the intersections of Black queerness, allowing the underrepresented to take up space, be seen, and be heard.

Terrell Brooke (he/him) is an interdisciplinary artist based in Los Angeles who works with body movement, sound design/experimentation, and vocal exercise to explore BIPOC queer feminist theory. Terrell’s most recent works, from rhythmic multi-genre sets to abstracted soundscapes, seek to explore notions of resiliency and femme embodiment and to amplify queer narratives.

C. Riley Snorton is a writer, scholar, and advocate. He is the author of Nobody is Supposed to Know: Black Sexuality on the Down Low (University of Minnesota Press, 2014) and Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (University of Minnesota Press, 2017). He is also the co-editor of Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value (MIT Press, 2020).

Texas isaiah Resources, References & Inspirations

Resources, References & Inspirations

Please explore the following materials offered by Texas Isaiah and his conversation partners.

Reading List by Texas Isaiah

Texas Isaiah Links

2021 AIR Funder Credits

The Studio Museum in Harlem’s Artist-in-Residence program is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts; Joy of Giving Something; Robert Lehman Foundation; New York State Council on the Arts; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Jerome Foundation; Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation; and by endowments established by the Andrea Frank Foundation; the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Trust; and Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

Digital programming is made possible thanks to support provided by the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation’s Frankenthaler Digital Initiative.

Additional support is generously provided by The New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

Online