A Meditative Curriculum

Inspired by filmmaker Garrett Bradley’s interest in archival absences and her film America (2019), which reimagines scenes of Black life from lost feature-length films made in the United States between 1912 and 1929, Memories for the Future invites audiences to use sound and moving image to evoke the places, people, and stories that have been lost or left behind, in order to transform our collective history and future.

This self-guided, self-paced resource contains several offerings for how to engage with and understand film, as well as activations that delve into the film-making process. The term “meditative curriculum” indicates the intention of this guide to clear space for self-reflection and conversation within the space of learning and engagement.

The guiding questions and key themes around archives, historical erasure, and preservation of memory in this meditative curriculum are designed to be adapted and expanded by teachers, educators, families, and guardians. Though suggested activations can be done individually, we encourage you to use this guide to foster intentional dialogue and intergenerational conversations by learning and creating together.

Guiding Reflection Questions

- What is the echo of our existence?

- What do we leave behind in our wake?

- In what ways can you be in conversation with past and future versions of the self?

- How could film make visible the fragments of your life you no longer have access to?

- How do our bodies consider the ways they exist in time and space?

- What memory of the self will you leave for others to consume?

- How can the documentation of your memory be an adoration to your being?

- How does reflection speak to permanence?

Suggested Materials:

- Journal and Writing Instruments

- Image and Audio Recording Device (Camera, Phone, Tablet, Camcorder, DSLR)

- Image Editing Device (Phone, Desktop Computer or, Laptop)

- Desktop Editing Software (iMovie, Quick Time Player, Final Cut, Premiere)

- Phone Editing Software (Magisto, WeVideo, Adobe Express, Clips)

- Audio Editing Software (Audacity, Audio Cutter, Adobe Audition)

- Music Making Software (GarageBand, Pro Tools, Ableton Live)

- Analog Equipment (Cassette Players, Camcorder, Overhead and Film Projectors)

- Personal Archive (Family Albums, Home Videos, Letters, Documents, Collections)

- Social Media Archive (Instagram Stories, Gifs, Tik Toks Videos, Camera Roll, Tweets)

- Virtual Meeting Platforms (Zoom, Google Meets/Hangouts, Flip Grid)

Culture & Context

Familiarize yourself with collections of existing archives and consider what stories archives tell about history.

Archives are repositories for information and materials that tell a story. Garrett Bradley began America (2019) through her research of feature films at the Library of Congress. In America, Bradley reimagines the lost narratives of Black figures during the early twentieth century, questioning what the gaps of an archive say about cultural legacy and seeking to provide us with re-envisioned fragments of history. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, located in Harlem, opened in 1925 with the collection of Afro-Puerto Rican historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Schomburg began his personal collection as a means to preserve materials that documented Black life in America.

We add to our personal archive regularly through social media such as Instagram, Tik-Tok, Gifs, and SnapChat. Consider personal archives and the many forms they take—family albums, home videos, social media, and personal letters. How do you physically engage with this material? Scroll or flip through any archives you have access to—which memories would you want to preserve?

In what ways do we archive our experiences?

What are the feelings that these collections conjure?

Are there gaps in your personal archive or experiences with people, places, and objects that you have lost access to?

Auditory History

Listen to the audio playlist from Projects: Garrett Bradley, in which Bradley, and lead actress Donna Crump, speak on the making of America and its depiction of US history.

As you listen to the audio playlist, note anything that stands out to you about how Bradley and Crump approached the project. The idea of loss or shining a light on overlooked histories is prevalent. Write down a few overlooked histories, personal or public, that you are interested in. Think about whether there are any songs that remind you of the people, places, or times that those histories evoke. Afterward, listen to the playlist and reflect on how the small, private histories these songs illuminate live within a larger timeline.

How might you reanimate something that has been lost?

While engaging with your own archives, are there moments when memory fails you?

Are there songs that sometimes take the place of memory?

Activation: Writing & Creation

Reflect on your connection with memory, experience, and archive through stream-of-conscious writing.

Set a timer for two minutes. On a sheet of paper, begin a poem with, What is the burden of memory when… Allow yourself to write uninterrupted until time runs out. When finished, circle six words that stand out to you. Take a moment to imagine a sound that embodies each word, then create or find that sound in your environment and record it using the voice memo app on your phone—try to be mindful of all background interruptions. Write a few words to describe how those sounds make you feel. Repeat the process incorporating the following words into your poem, Lost, Breath, and Portal, setting a timer for two minutes after you write each time.

Afterwards, consider how you might create a visual and sonic representation of the emotions behind your poem.

Gather some objects or visual materials that you are interested in documenting. Consider why you chose those items, the stories they tell, and how they might convey your personal stories in a film. Then, organize them using the keywords and sounds you identified. This can become an outline for a short film.

Next, review the archive of sounds you recorded, consider where you would add these sounds to your film to convey the emotions from your writing.

Will you use objects from your personal archive or a combination of related media? Consider why you are using those items, what stories do they tell and how will you engage with them throughout your film. Finally, use a device to record the materials you've collected while playing your recorded sounds in the background.

How might your video create a depiction of non-hierarchical time?

What specific aspect of your life do you want to explore?

What transitions are present that will take the viewer on a journey?

What would you like your viewer to feel if they were only to hear your film?

Activation: Archives & Healing

Find an image (still or video) that you find healing. Study the image and reflect on what drew you to it.

History often inspires artists. We can use our personal histories as a starting place to heal something within us, and use that to make something that could potentially heal others.

Find two more images to accompany the first one; go to a different source for at least one of the images. Once you’ve found three images, decide on how to order them. What story do the three images tell that is different from the initial image alone?

How can an image heal?

What imprint does an image leave on your spirit?

What does healing require?

How can a sequence tell a story?

TIP: Consider using analog equipment to physically engage with archival materials. If access to existing transparency film is available (35mm slides, 8mm film, transparency documents), overhead and film projectors allow you to enlarge and layer images within a physical space. Analog projectors can be found at local second-hand shops or reselling sites such as eBay and Craigslist.

Activation: Light

Look at the still and installation images from America. Write down five ways Bradley evokes certain moods through the use of light.

Artists often plan the use of light in their work, and it is especially critical to filmmaking and photographic media. Lighting guides the viewer's eyes toward important aspects in a film and helps to create the overall atmosphere.

Record a short video. Then record the same content but change the lighting.

How does the manipulation of light change mood?

What conversations does light open up?

What can darkness convey?

Activation: Shot Composition

Use photography as a stepping stone to understand how to make dynamic compositions.

Artists intentionally compose their shots using various techniques and testing multiple perspectives.

Central to Bradley’s practice is the attention to how an image immediately impacts the viewer. This compositional guide will get you started on formal techniques such as the rule of thirds or leading lines. Consider the relationship between the objects and people in your frame. Scan the corners for any unwanted obstructions and readjust if needed.

Take a casual photo of something around you. Then, using one of the techniques in the compositional guide, re-take the photo by moving the central subject (which could be a person or an object) to where the technique requires. Then, use the same technique and capture the subject via video.

Think about the following quote from Bradley: “When we think about what American symbols are, what American nostalgia is, what the aesthetics around Americana can be, a goal of mine, actually with all of my work, was for people to be able to freeze the film at any moment and that that image that's there could be a billboard.”

Once finished view the photos and video together. How does the subject change?

What makes an image powerful?

How does angle shift meaning? Power?

What connotations might we arrive at through the visual experience?

TIP: Experiment with accessible methods of recording such as a mobile device or computer. Using a tripod (camera) will allow you to stabilize your device while using a selfie stick (phone) will offer the freedom of motion. If professional camcorders or DSLRs are accessible, consider how to leverage the capabilities of those tools while planning your shots.

Activation: Online Collaboration

Utilize a contemporary platform such as Zoom, Google Meets, or Flip Grid to record a film by recording your meeting or shared screen.

The screen sharing function allows you to display images and videos from your desktop or web browser. Layering can be used effectively in creating a connection between your images and other materials.

You can also use video calling platforms to work together with long distance collaborators. For America, Bradley worked with sound artists in entirely different countries; Trevor Mathison is based in the United Kingdom, and Udit Duseja lives between London, England and Mumbai, India.

Choose a friend to collaborate with or put out an open call for collaborators on social media and see what you can make together.

Can you bend time and space by screen recording only in the digital? How can you make the virtual meeting space feel physical? What will another person's history bring to the story you can tell?What can you impart together that you could not convey alone?How will you honor the different talents and creative viewpoints each collaborator brings?Where can you bring your voice forward and where can you allow it to be in the background?

Activation: Sound and Score

Create an original film score that tells a story and provides a rhythm to visual imagery of your choice.

While working on America, Bradley considered what the sound of a silent film could be. Collaborating with composer Udit Duseja and artist Trevor Mathison, Bradley added to the sensorial experience through sonic work. When creating your score, consider how the sound and the images complement one another.

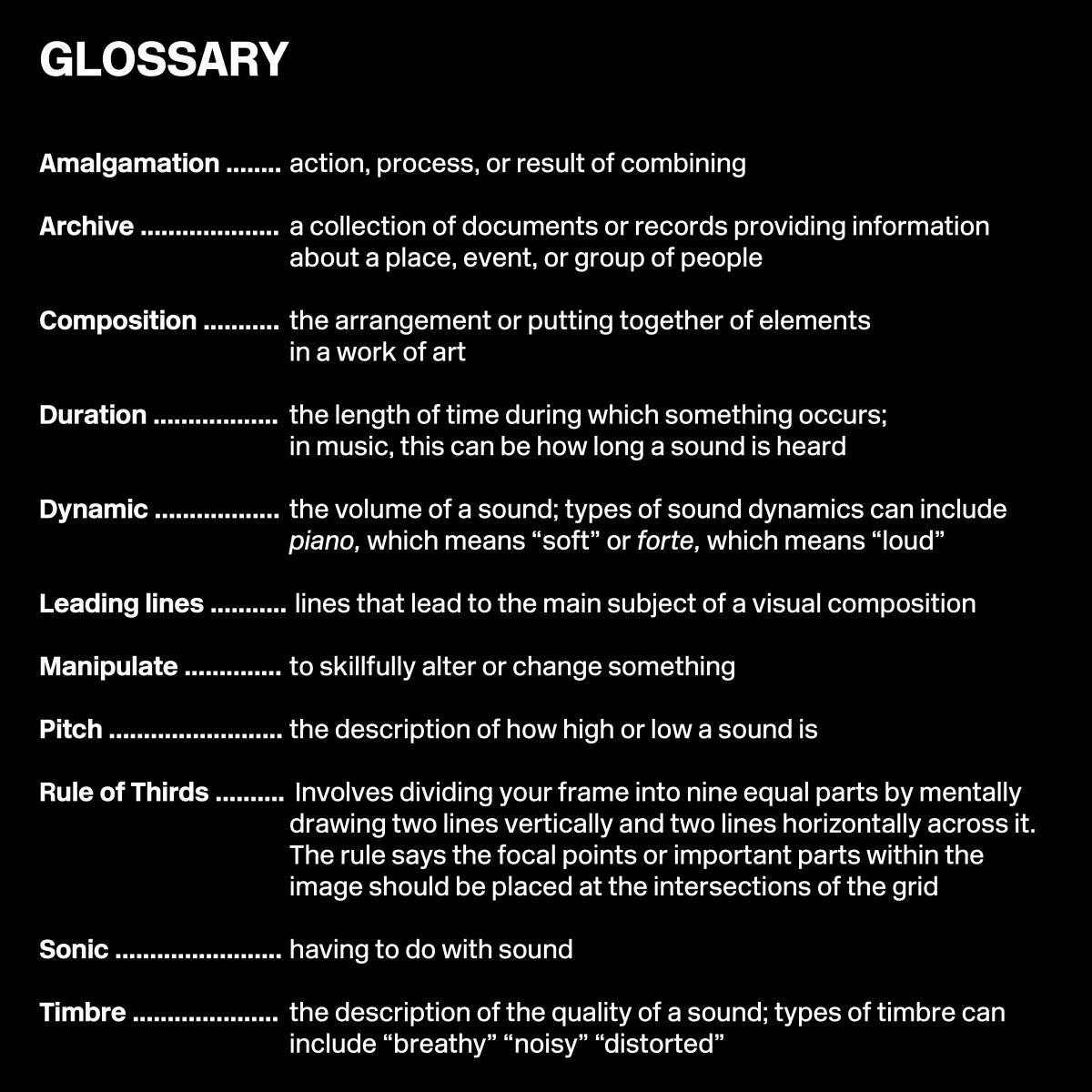

Researching and using existing audio in the collections of archives such as Freesound could also tap into feelings of nostalgia. Use audio editing software such as Audacity or music-making software such as GarageBand to create your score. How can you experiment with special effects, layering audio, pitch, duration, dynamics, and timbre to enrich your narrative visually and emotionally?

In what ways can an audio score also be a portrait of your life?

Are there any ambient sounds that act as portals to your home?

How does the sonic element reflect the lighting of your film? Review the archive of sounds you recorded. Are there any additional sounds that could help convey your narrative?

Activation: Editing and Audio

Edit a film by slicing together video clips and adding an audio overlay.

Film editing is the art of selecting and combining the shots to be sequenced as a film. Apps such as Magisto and WeVideo allow you to edit film directly on your phone. If using a computer or tablet, iMovie or Adobe Spark will provide you with more advanced editing capabilities.

How can you embody the emotions present through your choice of shots and how they transition?

How does pacing convey meaning and move a story along?

When should sound come together with image and when should it depart?

Reflection

What connections does your film make to concepts of collective identity?

How is your film illuminating parts of the self wanting to be seen?

How does your use of sound capture more than what is seen in the visuals of your film?

Where might this film live and why?

If unearthed fifty years from now, how might viewers engage with the film and its content?

How is time broken, altered, and remade in your film?

How do still images and motion-based imagery reinterpret the act of remembrance for you?

Resources

Archives:

- Interference Archive

Exploring the relationship between cultural production and social movements - Internet Archive

Non-profit digital library offering free universal access to all knowledge - List of Digitized Archival Holdings of African American History Organized by State

- Library of Congress

World’s largest library containing more than 170 million items - Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

Dedicated to the research and preservation of African American, African Diasporan, and African experiences - Freesound

A collaborative database of creative-commons licensed sound for musicians and sound lovers

Readings:

- Re-Imaging America

Artist and filmmaker Garrett Bradley in conversation with Thelma Golden and Legacy Russell - Librarians in the 21st Century: It is Becoming Impossible to Remain Neutral

By: Stacie Williams - Moving Toward a Reparative Archive: A Roadmap for a Holistic Approach to Disrupting Homogenous Histories in Academic Repositories and Creating Inclusive Spaces for Marginalized Voices

By: Lae’l Hughes-Watkins - Fighting ‘Erasure’

By: Parul Sehgal

Organizations: