Harlem Postcards

April 20–July 16, 2017

Recently I read a review of Cy Twombly written by Frank O’Hara in 1955. O’Hara wrote “the painting itself is the form,” and it reminded me of something I’ve been thinking in my studio: whether the beautiful and the political are not at odds, as some may claim, but entwined. Beauty simultaneously feeds and resists political action—one desires the other and opens a conversation, perhaps violently or, at times, very quietly. My paintings are layered over a long time with oil, impasto, and graphite. I often begin with a maple panel already in its frame, and make the painting within that limitation. Form is never indifferent, but rather it is useful—and at times critical—for opening perspective. In this way, architectural elements can help hold the intensity of feeling or history, so a viewer has a way in—like a doorway.

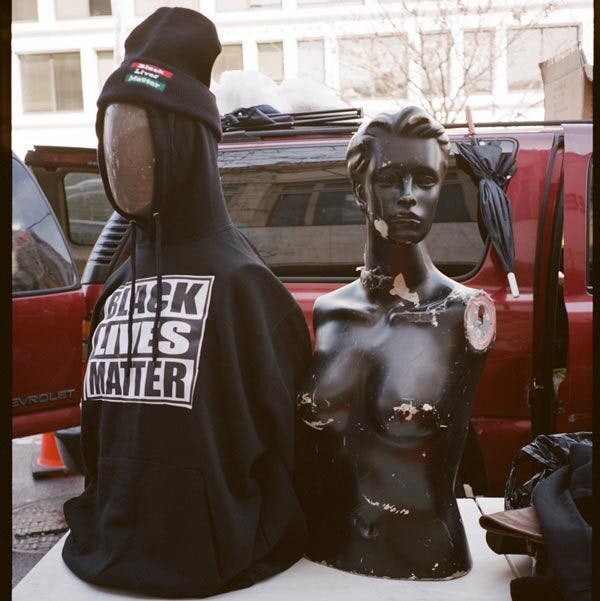

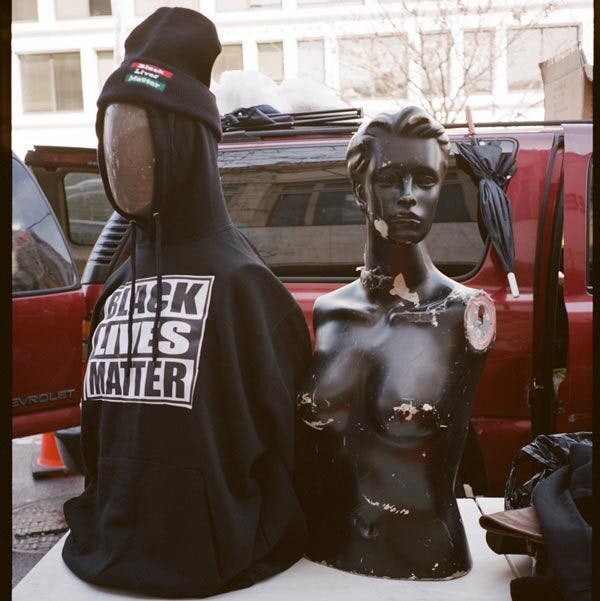

When I captured this image on 125th Street, I was interested in how this incidental arrangement could represent both a problematic commodification of activism and an urgent need for resistance. The Black Lives Matter merchandise hanging on a faceless Black mannequin also evokes Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, which, in both location and metaphor, navigates many of the same challenges Black Americans face today: lives of simultaneous hyper-visibility and invisibility.

By recontextualizing well-defined and documented ideas and display methods traditionally attributed to white people and their accompanying history, I hope to offer a different look or starting point for a conversation about Black history and people. Both the Black race and the white race are American constructs that are maintained to protect white interests. If these ideas are constructs, then is the history based on them a construct as well? Is this history as malleable as the lies we are fed in retellings of events past? What if we were given a different starting point? What if the language that has been developed to talk about whiteness was used to describe Blackness? What would that look like? Once placed b(l)ack in their appropriate historical context, do these new images and items carry the same message? When we look at each other our histories collide and build new ones, from which we can depart anew.

The refusal to perform alludes to a history of resistance. This type of activity is mirrored in images that remain offline and unshared. A “dignity image” is a personal image that has not been shared on social media. In an attention economy in which people are only worth the images they share, the images withheld from circulation—whether out of sentimentality or security—may be important tools for retaining dignity and identity. Marvellous Iheukwumere is a resident of Harlem and this is her dignity image. “I'm a Nigerian woman, and I'm passionate about my culture because it is so rich and has given me a great perspective on life,” she says. “In this picture, I'm wearing a custom-made top that signifies my cultural heritage. Even though I've lived in Harlem for seven years, I take my culture everywhere I go.”

Harlem Postcards

April 20–July 16, 2017

Recently I read a review of Cy Twombly written by Frank O’Hara in 1955. O’Hara wrote “the painting itself is the form,” and it reminded me of something I’ve been thinking in my studio: whether the beautiful and the political are not at odds, as some may claim, but entwined. Beauty simultaneously feeds and resists political action—one desires the other and opens a conversation, perhaps violently or, at times, very quietly. My paintings are layered over a long time with oil, impasto, and graphite. I often begin with a maple panel already in its frame, and make the painting within that limitation. Form is never indifferent, but rather it is useful—and at times critical—for opening perspective. In this way, architectural elements can help hold the intensity of feeling or history, so a viewer has a way in—like a doorway.

When I captured this image on 125th Street, I was interested in how this incidental arrangement could represent both a problematic commodification of activism and an urgent need for resistance. The Black Lives Matter merchandise hanging on a faceless Black mannequin also evokes Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, which, in both location and metaphor, navigates many of the same challenges Black Americans face today: lives of simultaneous hyper-visibility and invisibility.

By recontextualizing well-defined and documented ideas and display methods traditionally attributed to white people and their accompanying history, I hope to offer a different look or starting point for a conversation about Black history and people. Both the Black race and the white race are American constructs that are maintained to protect white interests. If these ideas are constructs, then is the history based on them a construct as well? Is this history as malleable as the lies we are fed in retellings of events past? What if we were given a different starting point? What if the language that has been developed to talk about whiteness was used to describe Blackness? What would that look like? Once placed b(l)ack in their appropriate historical context, do these new images and items carry the same message? When we look at each other our histories collide and build new ones, from which we can depart anew.

The refusal to perform alludes to a history of resistance. This type of activity is mirrored in images that remain offline and unshared. A “dignity image” is a personal image that has not been shared on social media. In an attention economy in which people are only worth the images they share, the images withheld from circulation—whether out of sentimentality or security—may be important tools for retaining dignity and identity. Marvellous Iheukwumere is a resident of Harlem and this is her dignity image. “I'm a Nigerian woman, and I'm passionate about my culture because it is so rich and has given me a great perspective on life,” she says. “In this picture, I'm wearing a custom-made top that signifies my cultural heritage. Even though I've lived in Harlem for seven years, I take my culture everywhere I go.”