New Works in the Collection

Brandon Ndife1 artwork online

Jadé Fadojutimi1 artwork online

Jean-Michel Basquiat1 artwork online

2023–24 Artist-in-Residence Open Studios

May 4, 2024, 12:30–4:00 pm

Zoë Pulley

Open Studio

Works on Loan: 2023–24

09.01.23-12.31.24

Art Leadership Praxis

Announcement

New Works in the Collection

Brandon Ndife1 artwork online

Jadé Fadojutimi1 artwork online

Jean-Michel Basquiat1 artwork online

sonia louise davis

Open Studio

Between matter and memory Expanding the Walls 2023

August 2, 2023–July 18, 2024

Malcolm Peacock

Open Studio

One People Unite

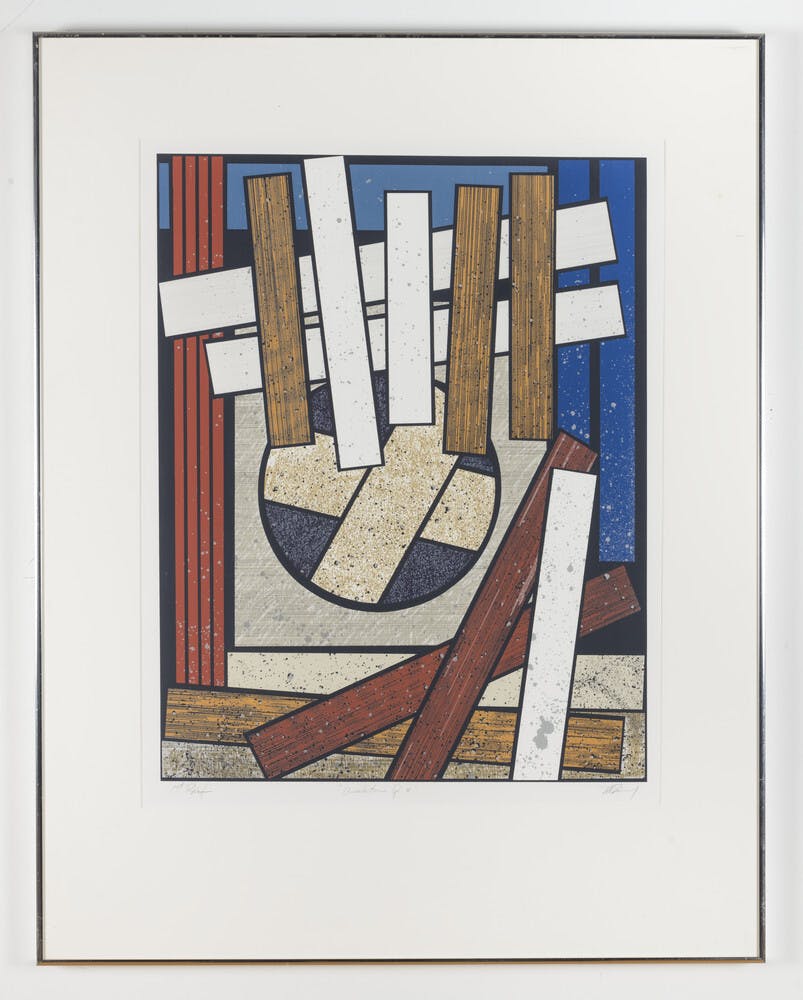

The Cover of Our Fall/Winter 2023 Issue of Studio Magazine